The crisis of neoliberalism is also a crisis of -to use the title of Guy Debord’s seminal 1967 book- the society of the spectacle that is at its heart. In such a climate Harun Farocki’s work has an increasingly large and diverse audience as it strives to analyze the ways moving images and cameras are imbricated in our everyday lives. His works tend to denaturalise moving images. This year alone the late German filmmaker Harun Farocki (1944-2014) was the subject of two major retrospectives, one in Paris at the Centre Pompidou and the other in New York City at Anthology Film Archives.

Born in Czechoslovakia, Farocki lived and worked primarily in West Germany. He made few feature films but prodigiously authored short films and later on video installations. Like the filmmakers of the French New Wave he is identified with a magazine in which he began by writing on film (Filmkritik) but unlike the filmmakers of the New Wave he continued to write on film–including, notably, a book on Jean Luc Godard that he co-authored with Kaja Silverman (Speaking About Godard, 1998). His work crossed into the domains and discursive practices of film, fine arts and academia.

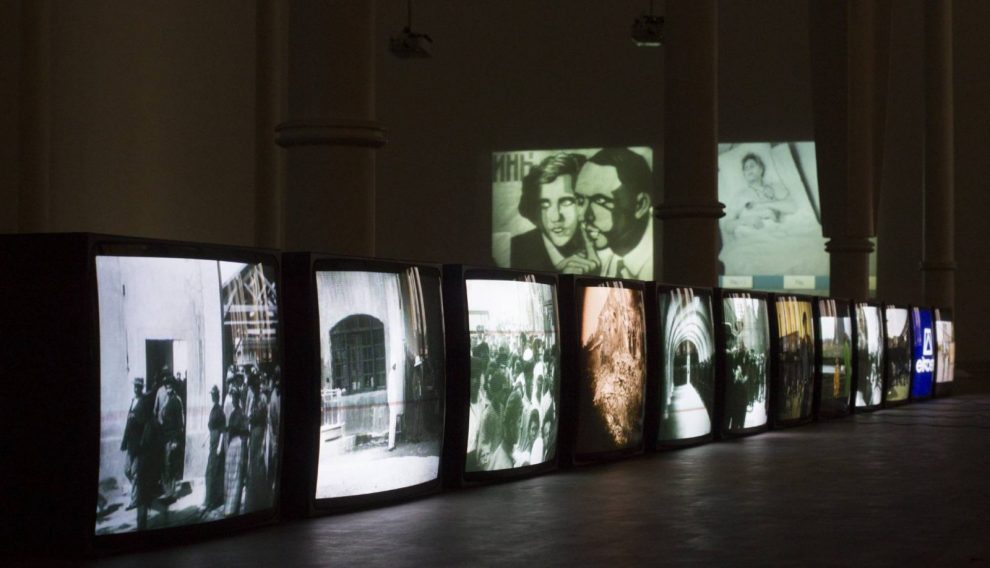

From an early age, Farocki imagined a dictionary of film that would isolate distinctive visual tropes. His film Workers leaving the factory (Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik, 1995), for instance, starts with one of the earliest scenes to be recorded on film: Workers Leaving the Lumiére Factory (1895). To this scene Farucki connects a series of scenes from the archives of world cinema showing workers leaving factories, mentioning in his commentary that this kind of scenes are comparatively rare, with film being generally focused on representing leisure time. In this work, Farucki notes that the scenes captured by the Lumière brothers resemble the framing of what would now be footage taken by a surveillance camera. He applies this concept in his video installation I Thought I Saw Prisoners (Ich Glaubte Gefangene Zu Sehen, 2000), where he repurposes video surveillance images that were intended for use only within a prison system to foreground their effect upon the way guards and prisoners interact. At one point the guards use data on each prisoner to select pairs likely to fight, when they are placed in the exercise yard at the same time, and then bet on who the eventual winner will be–like combatants in a video game. In Eye/Machine III (Auge/Maschine III, 2003) he uses images from the Gulf War taken by cruise missiles just as they hit their targets–images that are even more divorced from human authorship or responsibility.

This use of readily available archives to contrast and compare specific moments in film has changed radically in the last twenty years. It has gone from being an activity that required access to institutions carrying out such archiving to being one requiring access to collections of films accessible over the internet, some of them free. Consumers of popular culture, as well, have become accustomed to viewing their favorite scenes at will, bypassing the need to sit in the cinema and see the entire film. As Laura Mulvey points out in her book Death 24 X A Second (2006), this has transformed how we think about and make film. Farocki relatively early on harnessed this new ubiquity of the film archive to undertake and speculate about film as a series of iterations.

His films always engage his own powers of critical analysis and elicit his viewer to do the same. In his video Words/Titles, Images/Shock, A Conversation with Vilém Flusser (Schlagworte, Schlagbilder, Ein Gespräch Mit Vilém Flusser, 1986) on camera Farocki and the media theorist Vilém Flusser dissect the semiotics of a front cover of the German tabloid Bild Zeitung. Farouk’s work often appears to embrace a kind of positivist project of delineating the social role of moving images. However his own subjective position constantly reimmerges on the margins of his work. The Expression of Hands (Der Ausdruck der Hände, 1997), for example, shows multiple scenes of hands but on the margin of the frame we find Farocki’s own hands as he sits at the editing table. The persistence of an indexical trace of his own personal experience and position in relation to the work created by him prevents his work from being reduced to the positivism he might otherwise appear to embrace. It calls us to acknowledge our own subjectivity as we try to make moving images about the society of the spectacle and speak about it as well.